Double-push skating on cross country skis

Mon, Apr 21, 2008 - By Mike Muha

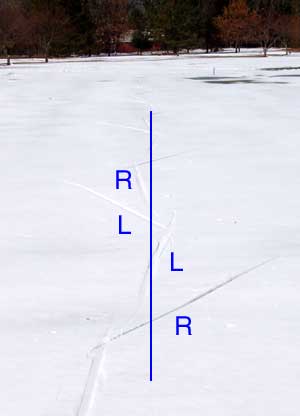

So what skate technique generated the ski tracks in the picture to the right? The double-push.

The double-push originated in the inline skate world. Traditional inline skating - as well as skating in the cross country ski world - works with alternating glides on the center of the wheels (flat of the ski) and pushing with the inside edge of the wheels (inside edge of the ski).

The double-push eliminates the glide phase by replacing it with an "underpush" on the outside edge. The recovery skate is placed on the outside edge and pushed underneath the body in the same direction as the other foot. It is is then steered back under the body in the other direction and begins pushing on the inside edge as in a normal skate. The weight of the skater (skier) is then transferred from the inside edge to the outside edge.

The advantage with doublepush is the skater is able to generate power during the part of the stroke that wasted simply gliding. And, as skiers know, a gliding skate (ski) is a slowing skate (ski).

The double-push

Before going further with this discussion, view the video below to see what a double-push looks like on inline skates (slow-motion video starts about 40 seconds into the clip). We'll then continue with a discussion of how double-push translates from inline skating to skating on skis. A couple things to look for in the video:

- Both skates point in the same direction at the initiation of the underpush.

- Both skates are pushing simultaneously for a brief period.

- The skater's center of gravity is precarious. If the underskate does not steer back under the body, the skater will fall.

Double push by Pascal Briand, World Champion Speed Skater, Team Salomon, coached by Christophe Audoire.

On the last snow of the ski season while I was trying out the Go Faster clap skate system, I played around with the double-push. I've been double-pushing on inline skates for several years, and I'd toyed with double-push on skis a little bit over the past two seasons, but this ski outing was the first time I focused on double-push. The photo is of tracks left toward the end of my session.

I've taken the first photo and drawn a line indicating (roughly) the location of my center of gravity. The R and L indicate my right and left skis. Notice that I'm pushing of the inside edge of my right ski, and that my left ski is pointing in the same direction as my right ski! My left ski is on it's outside edge and I have body weight pushing the ski underneath my body.

I've taken the first photo and drawn a line indicating (roughly) the location of my center of gravity. The R and L indicate my right and left skis. Notice that I'm pushing of the inside edge of my right ski, and that my left ski is pointing in the same direction as my right ski! My left ski is on it's outside edge and I have body weight pushing the ski underneath my body.

If both skis continue to the right, I'll fall over to my left! If I were on inline skates, I'd simply steer the left skate to the left by pushing my heel out; the skate would begin curving to the right and back underneath my center of gravity.

Unfortunately, skis don't roll. You can carve a turn with skis, but not fast enough to keep from falling over.

To change direction, I had to unweight the left ski with a little hop. While unweighted, I could then turn the ski to the right and to its inside edge. You can see in the picture how the ski suddenly changes direction.

Now I'm skating off the left ski. My right ski comes down on the snow, angled to the left and on the its outside edge. As I get precariously close to falling over, I unweight the right ski with a little hop, angle it to the right, and rotate the ski over to its inside edge.

I timed the double-pole pole plant with the unweight, or more precisely, as I came down on the ski after unweighting, I simultaneously planted my poles in the the snow.

Jump skate vs. double-push

You may have heard the term "jump skate." A jump skate is not a double-push skate, but a double-push uses a jump skate. Sprinters will "jump" (hop or skip) off the snow so they can add more pressure to the ski when they land. Generally, the left ski still angles to the left both before and after the jump, the right ski to the right both before and after the jump.

During the double-push, the jump skate is used to both add power to the skate AND to change the direction of travel of the ski.

Although the "underski" pushes out from the outside edge, this is not the same as the old teaching technique of having your recovering skate ski land on its outside edge. This drill was designed to teach you to balance on one ski; the ski still angled to the "correct" side and you were never told to apply power to the outside edge.

Variation on a theme

Frankly, the double-push uses a lot of energy and requires great coordination and balance. Although Thomas Stöggl & Stefan Lindinger (see below) believe it is faster than traditional skiing, they believe the demands it makes on the skier limits the technique to start and finishing spurts in sprint events.

A variation of the double-push is to angle the recovering ski directly down the trail. The skier does not push off the outside edge of the recovery ski, but pointing it straight down the trail during the glide phase means the ski will travel further down the trail then it would if it were angled toward the trail edge. A jump skate or carving action would still be required to turn the ski on its inside edge and angle it out.

Should you try the double-push? It is an interesting exercise in balance and coordination. Using a clap binding/boot like Go Faster would make it easier. I think learning it inline skates first might be easier - but falling on snow is much preferred to falling on pavement...

Additional reading and viewing:

Final Words of the Week on the Double PushFri, Apr 13, 2007 - By Thomas StögglThe technique might be just applicable at start, finish-spurt and moderate uphills were you normally change to paddling. |

VideoGetting Started with the Double Push on Cross Country SkisThu, Apr 12, 2007 - By Ken Roberts I got the double push working on snow. This video is of my first time trying it on snow. My approach is to make a hop with my foot up in between those two pushes, and switch the aim of the ski while it's partly up in the air. I got the double push working on snow. This video is of my first time trying it on snow. My approach is to make a hop with my foot up in between those two pushes, and switch the aim of the ski while it's partly up in the air. |

|

So what IS the Double Push?Tue, Apr 10, 2007 - By Mike Muha The best way to understand the double push is to watch an inline skater - the double push originated as an inline technique. The best way to understand the double push is to watch an inline skater - the double push originated as an inline technique. |

|

Using the Double Push and Klap Skate, athletes were able to complete a 50m measurement track faster than using conventional skate technique.

Using the Double Push and Klap Skate, athletes were able to complete a 50m measurement track faster than using conventional skate technique.